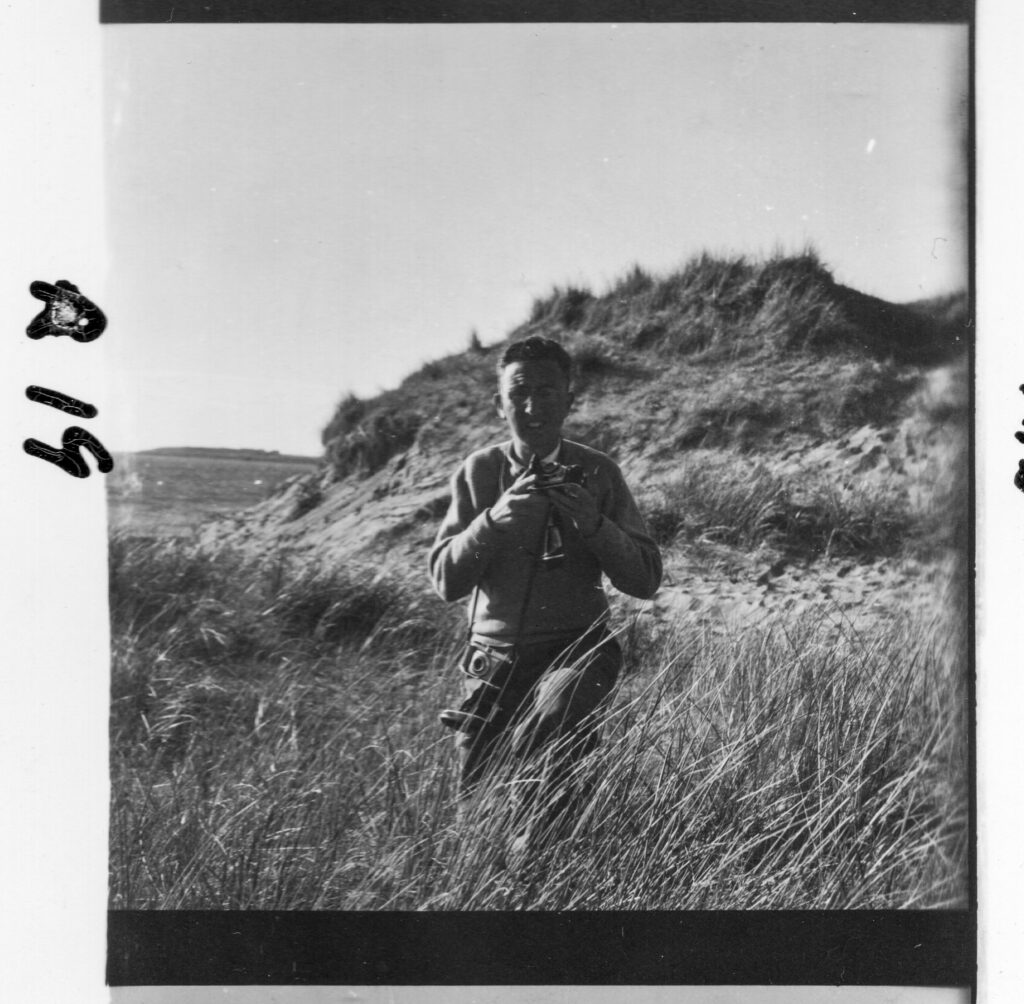

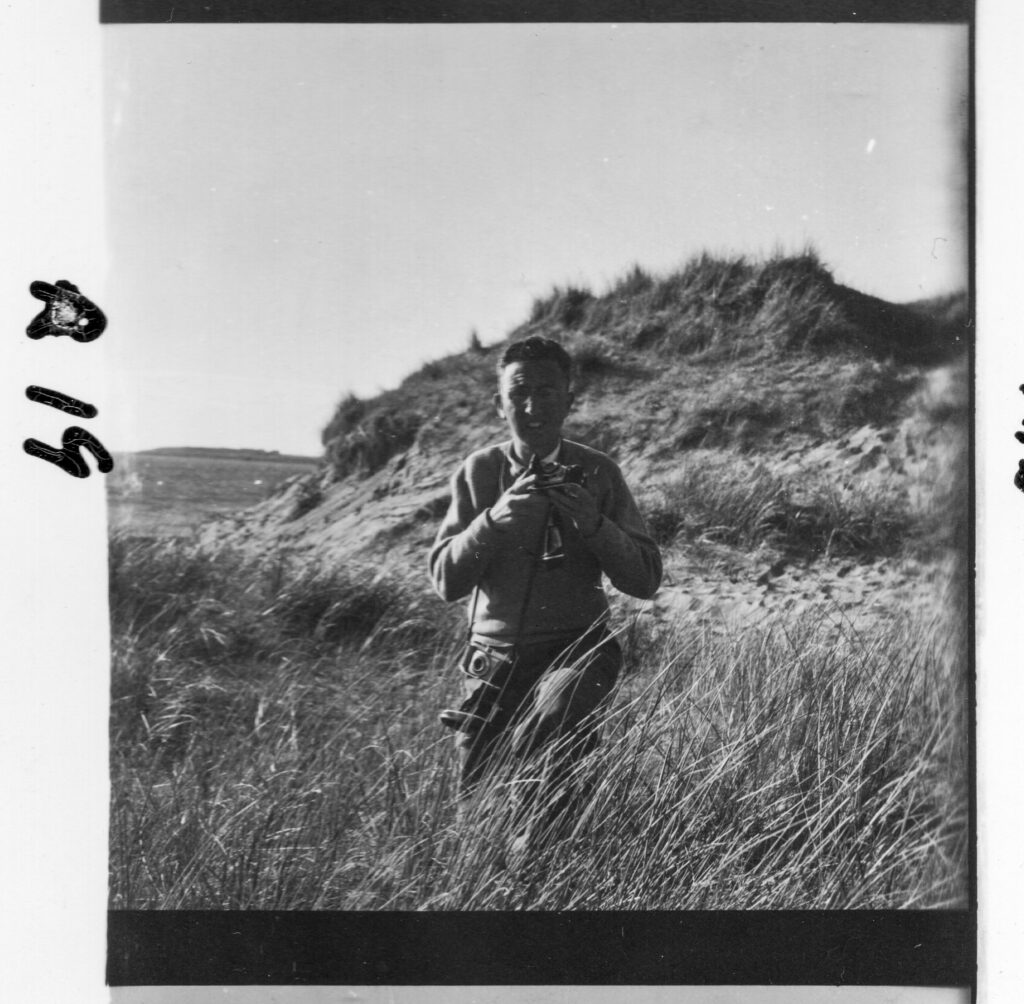

Tony Fitzmaurice, c. 1960, Killocrim Wrenboys perform in Listowel.

Tony Fitzmaurice photographed Wrenboys from various townlands in north Kerry performing in Listowel in 1960. Inspired by this I filmed two ‘Wrens’ on St Stephen’s Day 2025; the Ballybunion and Ballydonoghue Wren performing at Lisselton Cross and Dreoilín na Ríochta, Teach Siamsa Finuge moving from house to house in Killocrim, home to one of the groups Fitzmaurice photographed in 1960. The sound track features Seán Ahern as lead vocal on Aililiú an Dreoilín (Ah! The Wren), accompanied by the Siamsa Tíre performance company on a recording made in 1976. Frances Kennedy sings The Boys of Barr na Sráide (who hunted for the Wran). Both groups play a range of traditional and seasonal tunes, captured in passing on a shotgun mic.

An Dreoilín | The Wren 2025 is part of a larger work in progress about the extraordinary – but little known – Irish photographer Tony Fitzmaurice (1932-2019). The sight of a Strawboy walking down the road in Killocrim reminded me of a sketch in the Haddon Papers in Cambridge University Library. That sparked another idea which I develop in my Ballymaclinton Blog.

A race against time

Tony Fitzmaurice (1932-2019) of Ballybunion built an extraordinary collection of social documentary photographs over six decades, starting in 1954 when his parents gave him a present of a Kodak Retinette camera in recognition of his growing interest in photography. “Tony always had a camera at hand” wrote his cousin Kathy Reynolds on the website TONY’S PHOTO ARCHIVE, which she developed after Fitzmaurice’s widow Madeline asked her to “take the collection and decide what should be done with it”.

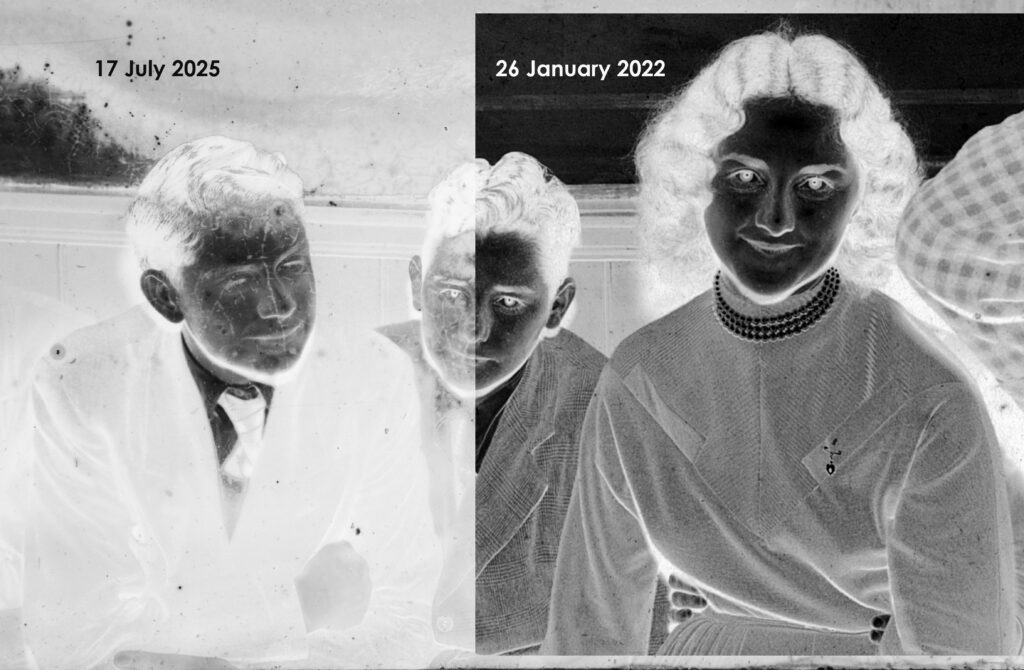

Tony Fitzmaurice c. 1960. Detail of a digital scan of an original contact sheet, which Fitzmaurice created in a darkroom by laying negatives on an 8X10 inch sheet of photographic paper and exposing them to light before developing the sheet as a positive photograph. Each image is numbered.

Kathy recalls how, as a child, she was fascinated by the dark-room her father’s first cousin built at the back of the kitchen and she attributes her interest in photography to him. Kathy and husband Steve – also a photographer – expected a lot of amateur landscape photography when they began going through the collection in 2019 and were astonished by the thousands of negatives that document social life in North Kerry. “Of particular interest” Kathy wrote “are the early photographs from the 1950’s and 1960’s that capture so well the town of Ballybunion along with the events and people of North Kerry”.

The most striking aspect of Fitzmaurice’s collection is that he was, in practice, photographer in residence in Ballybunion for almost six decades: the first three were taken up with black and white photography mainly, with a secondary line in colour slides that continued into the 2000s. After he retired from business in 2,000, Fitzmaurice began documenting the villages and holy wells of North Kerry. Indeed, Fitzmaurice recorded the changing backdrop of Ballybunion and its hinterland from the black and white fifties and sixties to the ‘Kodachrome’ Celtic Tiger. This collection within a collection featured in Kerry County Council’s festival Architecture Kerry 2025 – Bringing Life To Spaces.

Fitzmaurice was first and foremost a social documentary photographer but, unlike the wider movement in photography, he was an insider and his early work provides a unique perspective on rural Ireland in transition from the fifties to the sixties. It is a view that is characterised by familiarity, continuity and a startling directness of vision. The collection is, in essence, an intimate portrait of a community made up of 26,000 photographs shot over six decades; Fitzmaurice shot many of the early photos in local ballrooms where Fitzmaurice operated as “Tony – Photographer, Ballybunion“. This part of the collection constitutes an extraordinary collective portrait that challenges many of the stereotypical images of rural Ireland in the 1950s and 60s. It is also the part of the collection that is in need of urgent conservation.

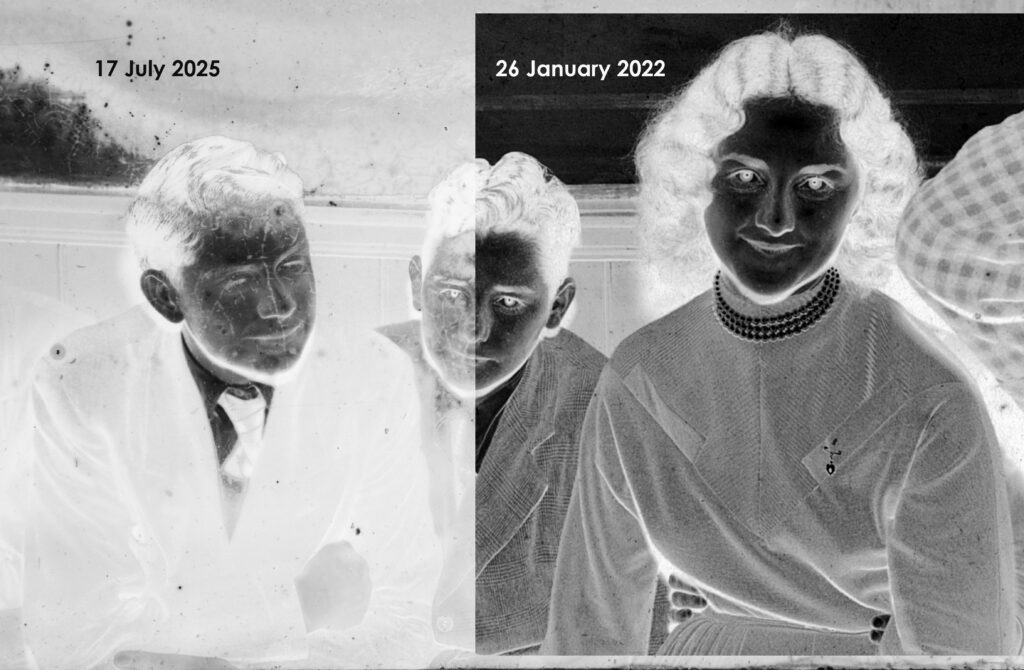

Tony Fitzmaurice, 1953, Ballybunion People # 33.

Fitzmaurice kept the negatives from each roll of film – six strips of six photographs per film usually – in folded manila envelopes that he packed tightly into six drawers of a small wooden cabinet. By the time of his death – sixty years after he began taking B&W photos – this had created two problems. The first is vinegar syndrome, a progressive and irreversible deterioration of the plastic film strip that releases acetic acid – hence the telltale vinegar smell. The second is a microbial growth that releases enzymes that consume the organic gelatine binder of the photographic layer. It is a lethal combination that has destroyed one third of the negatives and severely damaged another third.

Kathy and Steve began unpacking the collection in 2020 and had digitised almost six thousand images by 2025. They started with the most damaged images – the colour slides – and moved on to photographs that Fitzmaurice took at various dances and events. Their plan was place as many images as possible in the public domain and identify the people in them by creating website TONY’S PHOTO ARCHIVE as an online portal. They turned their attention to the long term future of the collection and looked for a home in or around Ballybunion. Kathy came across my work during Heritage Week 2024 and I met them in the Photographers’ Gallery in London in March 2025. They were looking to place the collective in a publicly accessible and not-for-profit archive. They donated the collection to Kerry Writers’ Museum in May 2025.

Preliminary conservation work revealed the extent of damage concealed in drawers that had not yet been scanned. The relentless progress of vinegar syndrome can be seen in the deterioration in negatives Kathy and Steve scanned three years before (see below). However, even the most damaged strips contain striking images that can be scanned and our priority now is to save these images. It’s a race against time.

&

Tony Fitzmaurice, 1953, Ballybunion People © Kerry Writers’ Museum

Kerry Writers’ Museum marks International Museum Day on Sunday 18 May with a public event celebrating the acquisition of three very important collections.

A major Heritage Council award has made it possible for the museum to acquire Jimmy Deenihan’s remarkable library of North Kerry Literary Trust video recordings of Kerry writers and their associates. Kathy Reynold has gifted Tony Fitzmaurice’s collection of over 26,000 world class social documentary photographs shot in and around Ballybunion in from 1954 on wards. Leo Finucane will gift a collection of material created over an extraordinary career as a filmmaker based in Moyvane.

Kerry Writers’ Museum received €47,750 from the Heritage Council to continue recovering and archiving films shot in rural north Kerry. This funding will enable the museum to develop a viewing library with trained staff to provide free, public access to these and other collections as they are archived and digitised. That places Kerry Writers’ Museum at the forefront of a strategic drive to manage public engagement with archives like this at a local level.